Environmental Infrastructure Engineering

―What kind of research are you doing?

The research we do in our laboratory addresses several geoenvironmental issues. Among our goals is to predict the behavior of contaminants in the ground, develop effective and economical countermeasures for ground contamination, recycle by-products generated by construction projects and industrial operations, analyze the effects of rising ground temperature rises on geotechnical phenomena, and create efficient separation methods for disaster wastes.

We have been researching soil-bentonite mixture (SB) cutoff walls for contaminant containment for more than 20 years. Bentonite, a clayey soil, can swell when it comes into contact with water. Due to the swelling of the bentonite in SB, the pores in the SB are filled, resulting in SB cutoff walls with high barrier performance. To improve the reliability of SB cutoff walls, we have studied their soundness against earthquakes, solute transport, selfhealing property, and so on. Additionally, we are conducting extensive research on excavated soils and rocks containing geogenic contaminants. Subterranean construction generates large volumes of soils and rocks. While geogenic contaminants are in relatively low concentrations in the excavated materials, the leaching concentrations of the toxic elements can slightly exceed the environmental standard values. Therefore, excavated soils and rocks should be effectively utilized considering the risks to the surrounding environment. Understanding the risk of contamination requires evaluating the leaching behavior of geogenic contaminants in excavated soil and rocks. For about 15 years now, our laboratory has been researching the leaching behavior of excavated soils and rocks. Our investigations aim to clarify the long-term leaching behavior of excavated soils and rocks which has yet to be fully understood. We explore various scenarios or geotechnical parameters (e.g., pore structure, saturation) that affect the leaching behavior of the materials.

―How do you run your laboratory?

Our laboratory is in charge of education in the Faculty of Engineering and the Graduate School of Engineering for civil engineering. Our activities are conducted together without distinction between the GSGES and the Engineering course. As of April 2023, the laboratory has six doctoral students, eleven master’s students, and four undergraduate students. Five of the master’s students are in the GSGES. Once a month, we hold a seminar to discuss the progress of our research activities.

―Tell us about the research your graduate students are doing.

Research in geoenvironmental engineering involves many experimentations. Soil is different depending on geology and location, so our research is difficult to generalize. Students are required to solve problems independently. Students need to be able to work with their hands, solve problems through trial and error, and confirm their results through repeating the experiments. For example, in our research on disaster waste recovery, we investigate how to efficiently separate soils from mixed disaster wastes and utilize the soils for construction. This will help reduce the amount of waste, as well as rapid restoration after a disaster. The students conducting this research were tasked to make their own experimental plans. They created simulated disaster waste by mixing wood and soil and conducted laboratory and onsite sieving tests. Their investigations showed that it is challenging to separate wood from the mixture if the mixture contains a large amount of fine-grained soil.

― Tell us what the atmosphere in the laboratory is like.

Students actively engage in research. Many students gather in the laboratory to conduct their experiments. Diversity is another important feature of our laboratory. The laboratory consists of Japanese and international students. Moreover, some doctoral students are working in Japanese construction companies while studying for their doctorate.

― What kind of areas do students move on to after they graduate from your laboratory?

Many students join the construction and infrastructure industry after graduation. Some become civil servants, while others continue with their research at universities or national research institutes. We are pleased to see them working to create a sustainable future using their expertise and experience in geoenvironmental engineering.(Department of Technology and Ecology)

Leaching tests for excavated soils and rocks

Leaching tests for excavated soils and rocks Site visit at a waste landfill

Site visit at a waste landfill-300x225.jpg) Microscopic observation

Microscopic observationUrban Infrastructure Design

―What kind of laboratory is it??

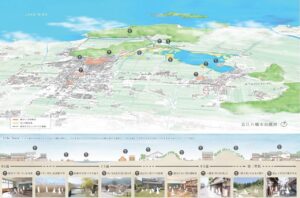

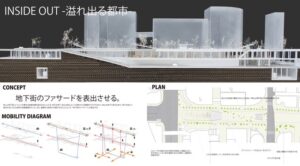

With “landscape” as a key word, this laboratory conducts exploration and practical research through an engineering approach on landscape and urban design and related planning methods for urban facilities and public spaces, encompassing urban planning. During the postwar high-growth period of the Showa era (1926-1989), the rapid development of cities and national land, such as the construction of highways, and the widespread use of concrete and steel gave birth to free forms. At the same time, however, the shape of cities changed in an uncontrolled manner, and a research field arose within the field of civil engineering to consider how to construct and design facilities to beautify urban landscapes like those in developed countries. In the JSCE (Japan Society of Civil Engineers), there are several fields of activity such as civil engineering planning, landscape and urban design, and civil engineering history. Among these, the field of landscape design is a fusion research area that integrates the fields of architecture and landscape architecture with urban planning. In our laboratory, we have expanded the scope of our research not only to urban facilities, but also to the landscaping of entire cities, including open spaces such as gardens and plazas, as well as buildings such as train stations. This is because, to make a city beautiful, it is necessary to synthesize the many objects of which it consists. It is also necessary to consider not only the value of beauty, but also the social structure and usage of the city so that people can lead vibrant social lives and engage in cultural and economic activities. If we do not take into account people’s vitality, local communities, and management, cities will decline. In view of the many challenges we face such as global environmental issues, population decline and the aging society, natural disasters, and infectious disease problems, research into the state of Japanese cities is a task whose goals should be pursued quickly within the span of long-term urban development

―What kind of research do you do?

Basically, we explore the spatial and temporal structure of landscapes and the objectives of design and design methodologies to create cultural and beautiful landscapes. For example, we conduct research on the design process, management, form, and color of urban facilities and public spaces; research on natural mountain and river landscapes and urban vistas; and research on original landscapes and images expressed in literature. In particular, the mountainside and waterfront areas of Kyoto and its surrounding cities are a treasure trove of design, and we conduct topographical analysis and design surveys using graphic systems such as GIS (Geographic Information System) and CG (Computer Graphics) to carry out sophisticated research on spatial composition and design techniques. We are exploring spatial models, such as the maintenance of historical environments, from the historical background of their establishment, and attempting to reflect them in urban planning guidance and policy methods. We have also been studying the historical value of modern civil engineering heritage such as canals and streets. Furthermore, we have been conducting research on disaster and local community level issues by utilizing various methods such as social network analysis and fieldwork techniques

―How is the laboratory run?

There are 25 people in the entire laboratory, including the concurrently employed engineering students. There is one professor, one associate professor, one assistant professor, one secretary, three doctoral students, 12 master’s students, five undergraduate students (Civil, Environmental and Resources Engineering), and one special auditing student (from France). Student residence rooms are located on the Katsura Campus, and practical design and exercise work is conducted in the laboratory. Our faculty offices are located on the Yoshida Campus.

―What kind of research are your graduate students doing?

Some graduate students continue their undergraduate research and develop it further in the master’s program, while others take on new challenges. In each case, we emphasize the importance of students’ own initiative and will. Many of our graduates are active in public construction think tanks, consulting and design firms, general contractors, and as national and local public officials. They work in a public service capacity for the vitality of the nation and cities, and society also expects them to be immediately effective. Therefore, we believe that analytical thinking alone is not enough to benefit the world, and we are pursuing our research with the aim of finding social issues on our own and cultivating the creativity to come up with comprehensive solutions to them. (Department of Natural Resources)

Biodiversity Conservation

―What kind of research do you do?

The research area that Professor SETOGUCHI and Assistant Professor SAKAGUCHI are focusing on is the evolutionary biology of plants, based on plant systematics and phytogeography. In the past, we used to spend more than a third of the year conducting studies overseas, but recently, our research has become more Japan-centered. Japan stretches a long distance from north to south and has diverse environments, ranging from subpolar to subtropical zones. We hope to find interesting phenomena that are unique to the characteristics of the Japanese archipelago and explore how plants adapt themselves to such environments for evolution and survival. Associate Professor NISHIKAWA is doing very similar research into fauna, as opposed to flora. The fields in which he conducts his research center on East Asia, including Japan, and Southeast Asia.

A large percentage of the plants and animals we study are rich in diversity. We have conducted various activities such as conservation, collection and propagation for each animal and plant that we encounter in the course of our research, but, ultimately, somewhere along the way, we have realized that conservation has come to take up a full half of our work.

―What is unique about your laboratory?

When we joined the Hall of Global Environmental Research, we thought about what our defining characteristics were. Because we were working in biological diversity, diversity and evolutionary, and diversity conservation studies, “diversity” became our keyword.

Also, given our responsibilities in liberal arts courses, we try as much as possible to have each of our lecturers cover a broad range of areas. If we were to establish one single course like other faculties, we would all be covering the same field. Although the orientation of our research is heading in the same direction, in our biodiversity classes, our lecturers are also diverse, which we see as one of the distinctive characteristics of our laboratory.

―Tell us about the research your graduate students are doing.

Many of students seem to be more interested in evolution rather than conservation. Having said that, although they may be most interested in evolution when they first start their research, as they participate in conservation-related events, spend time in the laboratory, and become associate with the locals, some students become more aware of conservation and eventually end up involved in conservation to a certain extent, even as they continue to pursue evolutionary studies and biodiversity sciences. We do hope that the students in our laboratory will become more involved in conservation through such opportunities.

―What kind of areas do students move on to after they graduate from your laboratory?

Of those students who have completed their doctorates, most have found jobs at universities. Some graduates have joined consulting companies and others have started their own businesses, taking advantage of their research experience. Some postgraduate students want to set up their own companies, so we hope to see more students who will experience that kind of research a little more and work actively in society in that way.

In terms of conservation and the like, involvement with public administrations will take on increasing importance going forward. In particular, we hope to deepen the connections on the cultural front. We would like to see our graduates move into a greater variety of workplaces after they have gained research experience, such as teaching, public service, or in ordinary private-sector business. Ultimately, that will be the quickest way when it comes to conservation of biodiversity. More flexibility in various respects is what we are aiming for. (Department of Technology and Ecology)

Sustainable Rural Development

―How would you describe your laboratory?

Our Laboratory was originally launched as the Agricultural Landuse Planning in the Faculty of Agriculture. The name was later changed to the Laboratory of Rural Planning, and in 2011, we joined the Hall of Global Environmental Research and became the Laboratory of Sustainable Rural Development. There is an academic society called the Association of Rural Planning, and we have been involved in this field ever since it was established. In simple terms, rural planning is the study of problem-solving for rural communities. Basically, we start with problem-solving in the regions, making use of various concepts, theories, and approaches to come up with concrete plans and proposals. We develop planning theories, methods, schemes and the like, but we do not attempt to complete them all by ourselves. Instead, we adopt a more pragmatic approach, in which we will insatiably try anything that we think might be useful for problem solving. Out in the field, there are not only problems, but hints for solving them lying in wait for us to find them, so naturally, we place major importance on learning from the field.

Our laboratory works on a variety of issues, not only in Japan, but overseas as well. We endeavor to generate concrete solutions, but the harder we try, or the more we want to make a proposal that suits that particular area, the more we find that each area has its own peculiarities and systems vary substantially from country to country. An interdisciplinary approach has been adopted in the study of rural planning since its early stages, but research themes have tended to focus on the challenges of rural communities in Japan. For this reason, the field had fallen considerably behind in an international sense. In that respect, we believe our laboratory has an advantage.

―What kind of things do you research?

Our fieldwork centers on the areas around Kansai, but we do go to a variety of places. The kinds of themes we engage in include, for example, research into the development of community planning methodologies and the restructuring of local organizations. We regularly visit regional areas and assist with the development of plans and make proposals regarding schemes on an ongoing basis. We select various regions to suit each theme, such as rural community planning in Kobe City, tourism in Miyama-cho, and digitization in farming communities in Kameoka. Going forward, we hope to prioritize themes such as the development of regional models related to rural planning and basic research regarding workshops.

―How is your laboratory run?

The laboratory has a total of 29 members, including one professor, two associate professors, one assistant professor, and three researchers, from Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Japan. We also have 13 Master’s students including students from Bangladesh, Indonesia, China, Taiwan, and South Korea. Because there are so many international students, our research themes are very diverse.

―What kind of research are the researchers and students conducting?

Our researchers are conducting research into future forecasting models in the areas of Marchais(street marckets), agriculture-welfare collaboration, and disaster prevention. The students’ research themes include improvement of disaster prevention resilience in local communities in metropolitan areas, the development of inbound tourism that takes the co-existence of multiple cultures into account, and workshops using 3D models. In particular, we are seeing rapid advancements in digitization in rural areas at the moment, such as what we call smart agriculture and is known as smart villages overseas, with ICT technologies rapidly spreading in farming communities. Seeing this as an opportunity, we are seeking to find solutions to the various problems that rural communities are currently facing, such as depopulation and the shortage of people willing to take over farming from aging farmers.